Article

Playing For Health | Part 1

Playing For Health | Part 1

By Del Herring

When you think of an artist, does an image of a playful soul pop into your head? Are artists known for their ravenous appetites for play? When you imagine an artist, is the artist flicking paint at a friend, or happily, whimsically, swirling paint on a canvas with a smile? Laughing with friends? Likely not. Grumpy intensity, passion, and smoldering angst are more likely to paint the initial image in your mind, riffing on Michelangelo smashing his (later repaired) sculpture Duomo Pietà.

Artists are known for angst and depression. Who but Van Gogh has an entire book about their ear? One can find details of Hemingway’s suicide, or the drug use and death of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Amy Winehouse, and Kurt Cobain, all at age 27. If play was a part of these artists’ lives, it certainly didn’t make the news.

Play is such an ephemeral–and sometimes private–thing that it may simply not be recorded as an aspect of an artist’s life. Would we know if van Gogh played with pigeons? If daVinci threw a ball for his dog? If Frida Kahlo teased her cat with a laser pointer? Okay, we know the last one, because she died in 1954 and the first laser was made in 1960, so no, she didn’t.

Play, like an organism too soft to be fossilized, rarely becomes part of the historical record, because the amount and type of play one takes on is considered unimportant whimsy. A spat between Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci made it into the historical record, but there is no mention of whether they played checkers. Only the artist’s product and scandalous misconduct are newsworthy.

Speaking of fossils, some artists are enjoying extremely long and productive lives. Bob Dylan (b. 1941) Paul McCartney (b. 1942), Mick Jagger (b. 1943), Keith Richards (also b.1943), and Elton John (b. 1947) are all still playing—music, at least. One might wonder what sets these long-lived artists apart from artists of a similar caliber with tragically short lives. Everyone in the list above struggled with drugs but got past them without falling into the “27” chasm. What might have given these creatives the resilience that let them skirt the chasm and reach instead for the sense of purpose that inspires both productivity and longevity?

Could the difference be something that adds resilience and flexibility, namely play?

There are many mental states familiar to artists wishing to enhance their creativity and performance, ranging from meditation to chemically induced mental diversions that all the artists above have acknowledged using. Play may be an unrecognized, underdeveloped, and underused tool for building and maintaining resilient mental health and creativity.

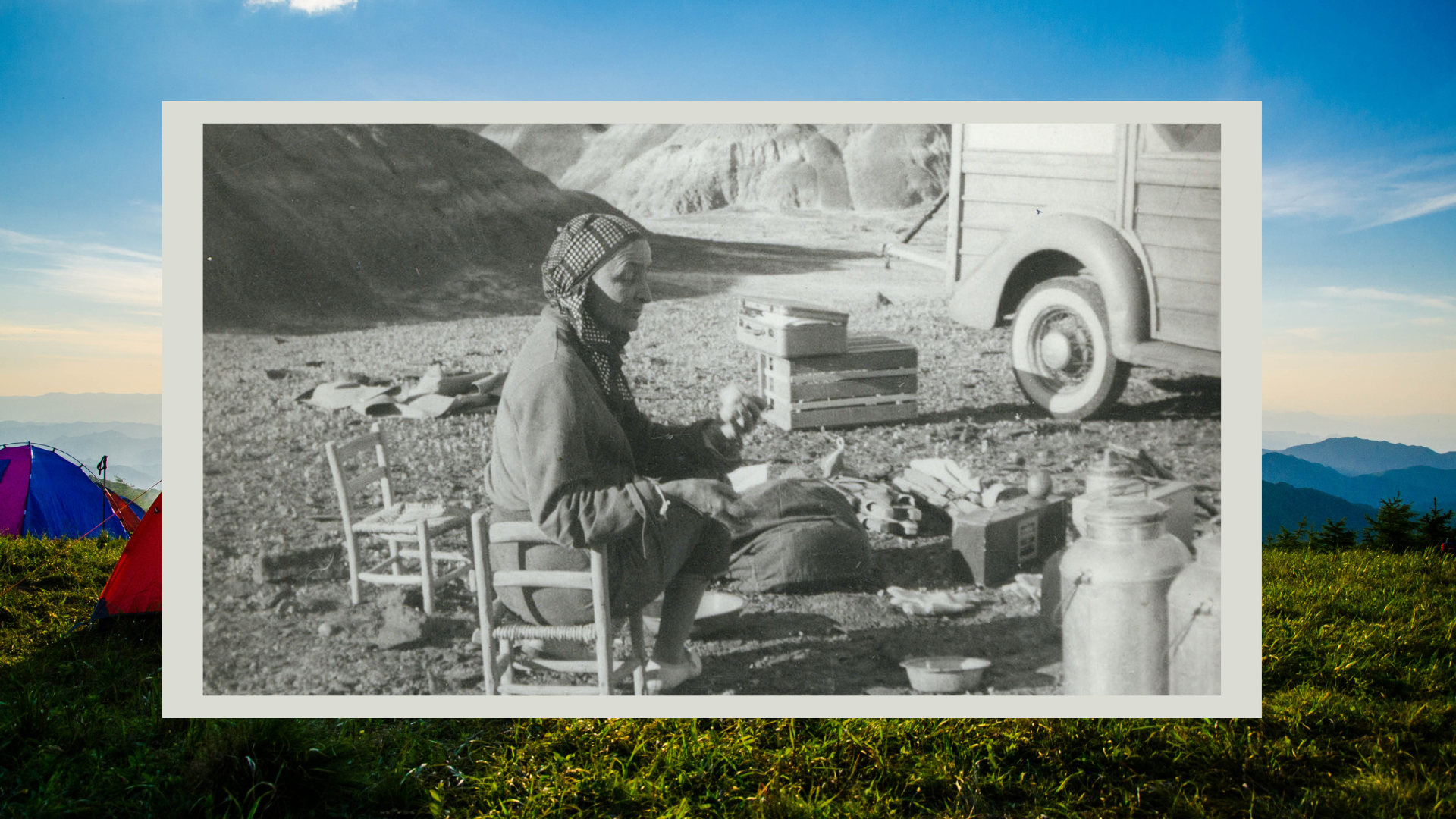

There are a few examples of artists at play. Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986) spent many of her 98 years camping, hiking, and exploring nature. Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) explored crafts and colorful clothing. Yayoi Kusama, now 95, hosted costume parties, and Andy Warhol (1928-1987) hosted elaborate gatherings at his studio, The Factory. Michelangelo, though not noted for play, may have exercised a playful side through poetry, as it appears he did not create his poetry with any intent to sell it or gain favor with his patrons.

Stuart Brown, MD, a psychiatrist who has studied play extensively and founded the National Institute for Play, defines play as “a state of mind that one has when absorbed in an activity that provides enjoyment and a suspension of sense of time.”

Can we highlight that?

Play is not an activity; it’s a state of mind.

Brown has studied play in humans, and with support from Jane Goodall, extended his studies into nonhuman animal play. Brown’s “play” state of mind resembles what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls flow: a mental state that may develop during work or play in which one has heightened engagement with a task, better productivity, and a reduced awareness of the passage of time.

Brown recognizes several personalities of play, and gives a celebrity example of each:

- Collector (Jay Leno)

- Competitor (Tom Brady)

- Creator/Artist (Steve Jobs)

- Director (Oprah Winfrey)

- Explorer (Jonas Salk)

- Joker (Jerry Seinfeld)

- Kinesthetic (Gillian Lynne)**

(**someone who feels playful primarily through movement, such as dance such as choreographer Gillian Lynne.)

These blend with some occupations, which underscores the value of enjoying one’s work. However, an association with work isn’t necessary or even encouraged. An overlap with work should not diminish the interest in, or the value of pure play.

Competitors play, but part of Brown’s definition of play stipulates that the outcome should be irrelevant—the activity itself is what encourages participation. Since the outcome is clearly important to the competitor, the personality might fit better in a different primary emotion one could call winning or validation.

Brown describes a spectrum of play; it’s not an all-or-nothing deal. Unlike kids, adults rarely entertain themselves with pure play. One of the primary rules of play—what makes it play and not work—is that the outcome is irrelevant to the enjoyment of the activity. This aspect of play separates the friendly family or neighborhood soccer or match or board game from true sport: people are there to play, not to win. Still, the outcome may matter to some; those who find a loss disappointing or revel in the glory of a win may need more practice playing.

Brown’s initial interest in play stemmed from his role as an investigator in one of the first mass shooter events, way back in 1966. He found the shooter’s childhood was strict and play was virtually forbidden. The more Brown looked, the more similar cases he found: when people grow up without play, they lose resilience and empathy. They resort to violence instead of a more peaceful, caring, empathic solution. He went as far as suggesting that parents let their kids rough-and-tumble play, because like wild animals, they instinctively know the difference between play fighting and real fighting. Play fighting exercises their trust, confidence, and communication, just as it does in non-human animals.

According to play researcher Jaak Panksepp, play is one of seven primitive emotions that are wired into dedicated circuits in the core of the human brain; the others are:

- Lust

- Rage

- Fear

- Panic

- Seeking

- Care